The current global climate finance agenda is insufficient to limit climate change. Especially expectations regarding the role that blended finance and domestic resource mobilization can play seem wildly optimistic.

Already in 2016, The Economist ran the headline “Trending: blending” (The Economist, 2016). Since then, the concept of blended finance has continued to gain traction. However, blended finance has not delivered on its promise. Back then, The Economist wrote that “few data exist on the scale and success of blended finance”. Today, the data shows that since 2016 private investments in low- and middle-income countries through blended finance has actually decreased.

Simultaneously, there seems to be too much optimism about the potential of domestic resource mobilization, i.e. the amount of capital that countries can accumulate by means of taxation. These resources have proven to be hard to increase in a relative benign macro-economic environment. With the current grim global economic outlook an increasing number of low-income countries is already in debt distress and increasingly impacted by the loss and damage of climate change itself.

In this blog we describe the current climate investment agenda and discuss the underlying assumptions. We conclude that these seem to be too optimistic for both domestic resource mobilization and blended finance. Dangerously so, as this prevents us from considering the additional sources of finance that are needed to provide climate investments at the scale and time needed.

The USD 1 trillion climate investment gap

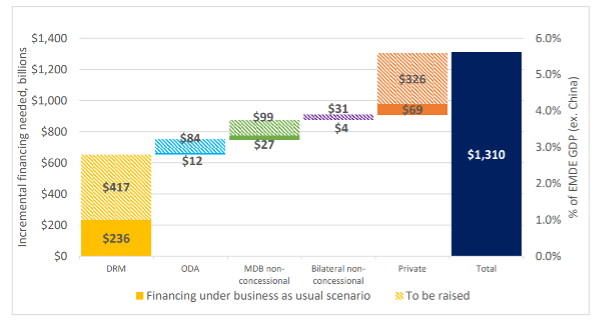

Currently, the climate finance gap for emerging and developing countries alone, excluding China, amounts to USD 1 trillion under the business as usual scenario. As figure 1 below shows, the main financial sources are expected to come from domestic resource mobilisation (USD 653 billion) and private finance (USD 395 billion), where private finance should be understood as part of blended finance (IHLEG, 2022; Bhattacharya et al., 2022).

Figure 1. The Grand Match financing strategy to close the climate finance gap between 2019-2025 (2019 USD)

Source: Bhattacharya et al. 2022

A recent report by Oxfam even estimates that the annual financing gap related to necessary investments in health, education, social protection and tackling climate change in low- and middle-income countries is USD 3.9 trillion (Oxfam, 2023).

Meanwhile, public finance is not pacing up as it should. In 2009, high-income countries pledged to help fund the energy transition in developing countries with an annual commitment of USD 100 billion. But in 2020, the overall figure was USD 83 billion (OECD, 2022). To get to this number, existing development assistance (ODA) money was relabelled as climate finance for developing countries. On top of that, only a third of the funds committed are in the form of grants (Oxfam, 2020).

The blending multiplier

Blended finance has gained the status of a silver bullet. According to the OECD, blended finance is “‘the strategic use of development finance for the mobilisation of additional finance towards sustainable development in developing countries’, with ‘additional finance’ referring primarily to commercial finance.’” (OECD 2018) The assumption is that public capital investments will lever private investments according to a certain ratio of the “blend”.

Many International Financial Institutions point to the relevance of blended finance as contributing to the closure of the global climate finance gap. The International Finance Corporation, part of the World Bank group, contends that “Blended Concessional Finance is one of the most significant tools that a development finance institution like IFC can use” (IFC, 2023). In 2019, the G20 leaders agreed that “international public and private finance for development as well as other innovative financing mechanisms, including blended finance, can play an important role in upscaling our collective efforts” (G20 Osaka leaders declaration, 2019). The Indonesian G20 chairmanship followed up this commitment with an annex to the Bali Leaders’ November declaration, which contained the G20 Principles to Scale up Blended Finance in Developing Countries, including Least Developed Countries and Small Island Developing States. Last but not least, blended finance was a key discussion point during the recent Spring meetings of the IMF and World Bank (IMF 2023a).

Blended finance assumes that a certain amount of public investments, if done properly, will result in a multiplied amount of private investments. However, the ratios assumed to yield the required threshold of private finance are quite astonishing in the light of recent developments.

In an IMF Staff Climate Note, the Amundi Planet Emerging Green One Fund, launched in collaboration with the International Finance Corporation, is referred to as a “representative deal”. At the time of its initiation, it was estimated that for every dollar of public funds, nine dollars of de-risked private finance could be crowded-in, thus assuming a 1:9 multiplier. Based on this, the IMF concluded that it “indicates the enormous potential of public money provided by a multilateral institution to channel private money to green projects (typically at 1:9 or even 1:10 ratios)” (IMF, 2022).

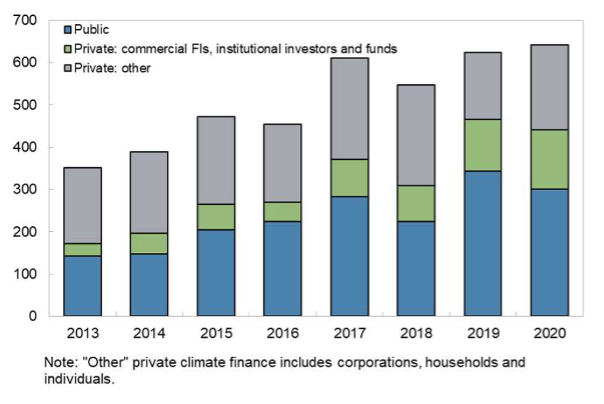

But can the Amundi fund multiplier potential be extrapolated to all blended finance initiatives? In reality the numbers appear to be vastly different. As figure 2 below shows, in 2020 total private finance constitutes only around 50% of global climate finance, with the rest being public finance (IMF, 2022).

Figure 2. Public and private climate finance by source globally

Source: Climate Policy Initiative in IMF 2022

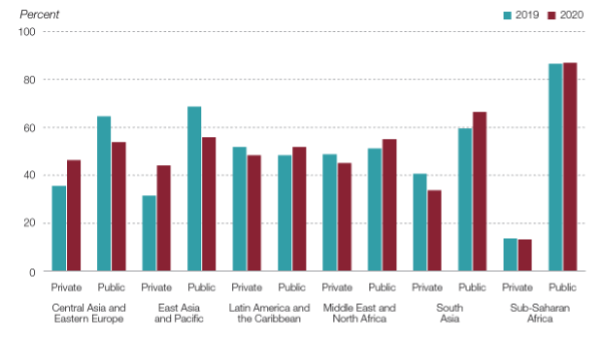

In the low-income regions where climate investments need to increase most strongly, even a public-private ratio of 1:1 is often not tenable. As figure 3 below shows in Asia most climate finance comes from public sources. In Sub-Saharan Africa even over 80% of climate finance comes from public sources (ADB, 2022).

Figure 3. Private and public finance in developing regions.

Source: African Development Bank 2022

Over the last years private investments through blended finance actually decreased in developing countries from USD 150 billion in 2012 to less than USD 100 billion in 2019 (Gallagher & Kozul-Wright, 2022). Between 2019 and 2021, there was only USD 14 billion of blended finance deals for low-income countries, less than half the volume seen in the previous three years (Tett, 2022). A recent report shows that MDBs raised USD 71.1 billion in private finance for lending to low- and middle-income countries in 2016, but only USD 63.3 billion in 2019 (Attridge, 2022). Similarly, the Global Infrastructure Facility, a body facilitating public-private partnerships supported by the G20 and the World Bank, has attracted only USD 47 billion since its establishment in 2014 (Global Infrastructure Facility, 2023).

Domestic resources: if only…

In the report of the Independent High-Level Expert Group on Climate Finance, domestic resource mobilisation also plays an important role (IHLEG, 2022). According to the IMF, Emerging Market and Developing Economies (EMDEs) can be expected to raise USD 236 billion of additional taxes by 2025 (Bhattacharya et al., 2022). Another estimate puts the potential to increase tax revenues at 3-7% of GDP for EMDEs (Benedek et al., 2021). This requires that EMDE’s implement relevant tax and administrative reforms tackling their sometimes very low tax rates and high levels of tax exemptions (Fenocchietto & Pessino, 2013). In this context, the IHLEG recommends an incremental tax effort of at least 2.7% of EMDEs’ GDP, equal to USD 650 billion, so an additional USD 417 billion by 2025 on top of IMF projections (Bhattacharya et al., 2022).

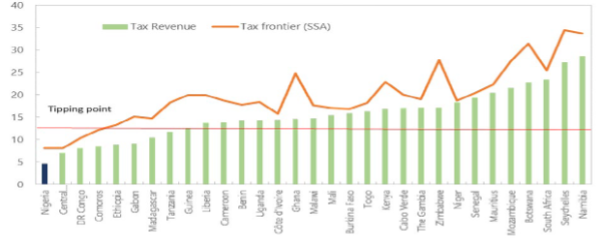

However, implementing and enforcing these kinds of reforms is challenging. EMDEs are renowned for administrative capacity constraints preventing them from addressing tax evasion and keeping avoidance under control (Abdel-Kader & De Mooij , 2020). Take Nigeria, for example, often critiqued for its highly inefficient tax systems. Nigeria’s tax capacity, defined as the highest level of tax revenue expected to be achieved given the country’s macroeconomic and institutional situation, is calculated to be at about 8-11% of GDP, while revenues, as of 2021, only reached 4.5% of GDP, as shown in Figure 4.

The inability of its government to effectively channel public funds towards much needed basic facilities reduces public trust, in turn lowering the population’s tax compliance (ICTD, 2019). Despite recent efforts to limit tax evasion and the commitment to raise the tax-to-GDP ratio to 15% by 2025 a raise in tax rates has not been planned yet (IMF, 2023b).

Figure 4. Potential and actual tax revenues African countries

Source: IMF 2023b

Studies on the projected development of tax-to-GDP ratios in EMDEs show that their tax revenues are expected to only slightly, but not significantly, increase (Hill et al., 2022). Moreover, some international support initiatives have already been in place, such as the Tax Inspectors Without Borders (TIWB) assistance programmes between 2012 and 2020. This has helped raise EMDEs’ tax revenues by a mere USD 537 million (OECD/UNDP, 2020). A figure far away from the necessary additional USD 417 billion in domestic resource mobilisation estimated in the IHLEG’s report.

Additionally, in response to the Russian invasion of Ukraine and subsequent spike in inflation levels, a global monetary tightening cycle has begun (World Bank, 2023). This resulted in capital outflows by the private sector from EMDEs, which is bound to substantially hinder these countries’ economic growth.

The simultaneous monetary and fiscal tightening policies across the globe impact developing countries and emerging economies disproportionally (UNCTAD, 2022). The current geo-monetary and -political situation makes the share of domestic resource mobilisation included in the IHLEG’s Grand Match finance strategy to close the finance gap seem even more unrealistic, especially given the high value of the dollar and the outstanding dollar denominated debt in the Global South. Out of the low-income countries eligible for special IMF support, currently 9 are in debt distress, while 27 are at high risk, 26 countries at moderate risk and 7 countries are at low risk (IMF, 2023c).

More realism is needed

Both the public and the private sector have not delivered on the promises made in the past. The USD 100 billion climate fund promise also pales in comparison to the current USD 1 trillion climate finance gap for low- and middle income countries, excluding China. The assumptions related to both domestic resource mobilisation and blended finance underlying the current global climate finance agenda seem overly optimistic. Dangerously so, as this prevents us from considering additional sources of finance that are needed to provide climate investments at the scale and time needed. Global policymakers should therefore critically examine these assumptions and explore additional sources of finance to close the global climate finance gap.

This blog post was written by Sara Murawski, Rens van Tilburg & Anna Ghilardi

The Sustainable Finance Lab (SFL) is collaborating on this topic with Beyond Bretton Woods (BBW), a platform co-founded by James Vaccaro (Re-Pattern) and Frank van Gansbeke (Middlebury College). SFL is heading the workstream on monetary solutions.

References

Abdel-Kader, K. & De Mooij, R. (2020). Tax Policy and Inclusive Growth. IMF Working Paper. https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/WP/Issues/2020/12/04/Tax-Policy-and-Inclusive-Growth-49902

ADB (2022). African Economic Outlook 2022. African Development Bank Group. https://www.afdb.org/en/knowledge/publications/african-economic-outlook

Attridge, S. (2022). The potentials and limitations of blended finance. In D. Schoenmaker & U. Volz (Eds.), Scaling Up Sustainable Finance and Investment in the Global South. CEPR Press. https://cepr.org/system/files/publication-files/175477- scaling_up_sustainable_finance_and_investment_in_the_global_south.pdf

Benedek, D., Gemayel, E., Senhadji, A., Tieman, A. (2021). A Post-Pandemic Assessment of the Sustainable Development Goals. IMF Staff Discussion Note. https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/Staff-Discussion-Notes/Issues/2021/04/27/A-Post-Pandemic-Assessment-of-the-Sustainable-Development-Goals-460076

Bhattacharya, A., Dooley, M., & Kharas, H. (2022). Financing a Big Investment Push in Emerging Markets and Developing Countries for Sustainable, Resilient and Inclusive Recovery and Growth. London: Grantham Research Institute on Climate Change and the Environment, and Washington, DC: Brookings Institution. https://www.lse.ac.uk/granthaminstitute/publication/financing-a-big-investment-push-in-emerging-markets-and-developing-economies/

Fenocchietto, R. & Pessino, C. (2013). Understanding Countries’ Tax Effort. IMF Working Paper. https://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/wp/2013/wp13244.pdf

Gallagher, K. P., & Kozul-Wright, R. (2021). The case for a new Bretton-Woods. John Wiley & Sons.

Global Infrastructure Facility. (2023). Global Infrastructure Facility. https://www.globalinfrafacility.org/

G20 (2019). G20 Osaka Leaders’ Declaration. G20. https://www.mofa.go.jp/policy/economy/g20_summit/osaka19/en/documents/final_g20_osaka_leaders_declaration.html

Hill, S., Jinjarak, Y., Park, D. (2022). How do Tax Revenues Respond to GDP Growth? Evidence from Developing Asia, 1998–2020. Asian Development Bank. https://www.adb.org/sites/default/files/institutional-document/782851/ado2022bp-tax-revenues-gdp-growth.pdf

IFC (2023). Blended Concessional Finance. International Finance Corporation, World Bank Group. https://www.ifc.org/wps/wcm/connect/topics_ext_content/ifc_external_corporate_site/bf

IMF (2023a). Chair’s Statement of Forty-Seventh Meeting of the IMFC. https://www.imf.org/en/News/Articles/2023/04/14/pr23120-chairs-statement-forty-seventh-meeting-of-the-imfc

IMF (2023b). Nigeria’s Tax Revenue Mobilization: Lessons from Successful Revenue Reform Episodes. IMF Country Report No. 23/94. https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/selected-issues-papers/Issues/2023/03/07/Nigerias-Tax-Revenue-Mobilization-Lessons-from-Successful-Revenue-Reform-Episodes-Nigeria-530628

IMF (2023c). List of LIC DSAs for PRGT-Eligible Countries As of February 28, 2023 https://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/dsa/dsalist.pdf

IMF (2022). Mobilizing Private Climate Financing in Emerging Market and Developing Economies. IMF Staff Climate Notes.

Neil McCulloch (2019). What Nigerians really think about tax. International Centre for Tax and Development – ICTD. https://www.ictd.ac/blog/what-nigerians-really-think-about-tax/

OECD (2018). OECD DAC Blended Finance Principles for Unlocking Commercial Finance for the Sustainable Development Goals. OECD. https://www.oecd.org/dac/financing-sustainable-development/development-finance-topics/OECD-Blended-Finance-Principles.pdf

OECD/UNDP (2020). Tax Inspectors Without Borders Annual Report 2020. OECD/UNDP. http://www.tiwb.org/resources/reports-case-studies/tax-inspectors-without-borders-annual-report-2020.pdf

OECD (2022). Statement by the OECD Secretary-General on climate finance trends to 2020. OECD. https://www.oecd.org/environment/statement-by-the-oecd-secretary-general-on-climate-finance-trends-to-2020.htm#:~:text=29%2F07%2F2022%20%2D%20Climate,increase%20from%202018%20to%202019.

Oxfam (2020). Climate Finance Shadow Report 2020. Assessing progress towards the $100 billion commitment. Oxfam. https://www.oxfam.org/en/research/climate-finance-shadow-report-2020

Oxfam (2023). False Economy: Financial wizardry won’t pay the bill for a fair and sustainable future. Oxfam. https://www.oxfam.org/en/press-releases/oxfam-warns-rich-country-financial-wizardry-puts-their-own-interests-ahead-worlds

Songwe, V., Stern, N., & Bhattacharya, A. (2022). Finance for climate action: Scaling up investment for climate and development. London: Grantham Research Institute on Climate Change and the Environment, London School of Economics and Political Science. https://www.lse.ac.uk/granthaminstitute/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/IHLEG-Finance-for-Climate-Action.pdf

Tett, G. (2022). The flood of green finance must be diverted from the west. Financial Times. https://www.ft.com/content/95c28b9e-7844-4ab7-8401-42d1cca133a8

The Economist (2016). Trending: blending. The Economist. https://www-economist-com.proxy.library.uu.nl/finance-and-economics/2016/04/23/trending-blendingg

UNCTAD (2022). Trade and Development Report 2022. Development prospects in a fractured world. UNCTAD. https://unctad.org/tdr2022

World Bank (2023). Global Economic Prospects. The World Bank Group. https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/server/api/core/bitstreams/254aba87-dfeb-5b5c-b00a-727d04ade275/content